Introduction

I've been a software engineer for quite some time now. Like many developers, the AI wave has become something utterly inescapable. Regardless of where I look, what I work on, or what I read, I can't get more than 10 minutes in before the topic of AI comes up.

Now don't get me wrong, I'm not anti AI. Staying relevant in tech requires a degree of adaptation. Agentic development will become a major part of how we work in software over the next decade, of that there can be little doubt. So I do what I suggest to anyone who will listen: make an effort to get good at using AI. That being said, I find myself needing some downtime from it on a daily basis.

There are also real dangers to using AI for everything. Problem solving is a skill that needs to be actively developed and practiced. The temptation to ask an LLM for assistance on every little problem can become overwhelming, and we are in real danger of creating a generation of people that are incapable of problem solving. Your brain is a muscle like any other, it needs to be worked or it will deteriorate.

Enter the simulation catalogue. This application/codebase is my down time from AI. At its heart, it's a Fortran physics engine that is indexed and made available via this app. All of it is written without AI. No code completions, no Claude Code. Nothing but pen and paper, a basic IDE and a few books. Distractions are turned off and U just focus on the mathematics and the code.

I'm a firm believer that solving difficult problems is an essential part of what it means to be human. Much like a sheep dog that requires a job to be happy, difficult problems provide a positive channel for our internal machinations. I sleep much better if I sit down after my kids are asleep and work on a few physics problems. Maybe that's just me.

Why Fortran?

Many people have asked: why Fortran? Why not just use NumPy? It's a valid question, and I have three good reasons to pick Fortran over Python.

- Performance - NumPy is impressively fast with vectorized operations. Still not as fast as Fortran, but not far off. However, many problems in physics can't be vectorized (Monte Carlo simulations are probably the most famous example of this). Sometimes, a good old fashioned loop is the only option, and Fortran is several orders of magnitude faster in these cases.

- Marketability - Fortran is still very much a marketable skill, one that's becoming increasingly rare. You'd be amazed at the amount of critical infrastructure code that is written in Fortran. It may be a niche market, but with the advent of AI, developing some niche skills is likely not a bad thing.

- Variety - I've been working on Python web apps since I started working in web development. Working with Fortran provides a nice change of scenery.

It's worth mentioning that I've worked with Fortran extensively in the past. I have a degree in Theoretical Physics, and much of the computational work that I did was in Fortran. It was also the first language I learned to program in, so it offers a certain sense of nostalgia.

Tech Stack

Now that the boring stuff is out of the way, let's focus on the engineering. I stand on the shoulders of giants; while the aim of this project is to work on being independent on external tools, there are a few I can't do without.

Fortran

The backbone of the physics engine. When it comes to numerical computing, Fortran is still king. It's incredibly quick, and much of what you need to work on physics problems is native to Fortran.

Golang

My go-to programming language. Unless I have a good reason to use something else, I use Golang. It's performant, has a ton of industry support, and provides an unmatched balance between development speed and code stability.

Terraform

Any infrastructure I need is always provisioned with Terraform. Its the only IaC solution I've ever needed, and the sheer number of providers it offers makes it a no brainer.

Vue

I'm not much of a FE engineer, but Vue has always been my go to. Many people will say "Just use React", and maybe they're right.

Kubernetes

All services are deployed on a Kubernetes cluster that I maintain on a Debian virtual machine somewhere in the cloud.

PostgreSQL

PostgreSQL handles all persistent data storage. My Kubernetes cluster already features a fully operational PostgreSQL cluster so this was a no brainer.

The Charged Particle in a Magnetic Field

There are a lot of problems I could have picked. In the end, I decided to go for something simple. A charged particle moving in a constant electro-magnetic field, with the addition of gravity.

This can easily be solved analytically. However, with the amount of engineering work that I had to do, I wanted to start with a problem that had a well defined solution, and that I was thoroughly familiar with. The equations of motion become:

where is the cyclotron frequency and is the drift velocity. A charged particle moving in this system will create a helical trajectory. The addition of gravity introduces a horizontal drift that can be counter-balanced with an appropriate electric field.

Implementation

Since this was the first simulation I wrote, there are three distinct problems to solve:

- Writing the simulation - handled in Fortran

- Running the simulation - handled in Golang

- Displaying the results - combination of Golang and Vue

The Simulation

The first part was the easiest, and took the least amount of time. It took me a few hours to get back up to speed with Fortran, but nothing major to report. The initial code featured a velocity verlet algorithm, but this produced unstable trajectories and was quickly replaced with a Boris Pusher integrator (more on that in a future article).

The Interface

In order to actually run the simulation, the Fortran code needed to be able to interface with the Golang components. This turned out to be the most difficult part. While technically not a difficult problem to solve for one simulation, defining an interface that works for ANY simulation in a clean, compact and repeatable manner is a completely different problem.

In the end, I settled on a fairly simple solution: TOML configuration files. All simulations were written in such a way that the first and only argument was the path to a TOML configuration file. This file would contain all the parameters and configuration settings required to run the simulation and produce any output artifacts. An example config looks like the following.

[parameters]

magnetic_field = [0.0, 0.0, 1.0]

electric_field = [0.0, 0.0, 0.0]

charge = 1.0

mass = 1.0

initial_position = [0.0, 0.0, 0.0]

initial_velocity = [1.0, 0.0, 0.0]

delta_t = 0.01

num_steps = 5000

[configuration]

output_dir = outputOn startup, each Fortran simulation would load the provided TOML file, and initialize all defined variables using the data in the file. The simulation would then run, and all outputs were saved in CSV format to an output folder specified in the config file. In (rough) Fortran:

program simulation

implicit none

real, dimension(3) :: parameter_1

real :: parameter_2

character(len=:), allocatable :: output_dir

character(len=256) :: output_path

real, dimension(10000, 3) :: output

integer :: i

call load_config()

do i=1, 10000

! execute simulation here

output(i, :) = [1.0, 2.0, 3.0]

end do

output_path = trim(output_dir)//'/'//'output.csv'

call write_csv(output_path, output)

contains

subroutine load_config()

character(len=256) :: config_path = "etc/default_config.toml"

integer :: n_args, stat

type(toml_table), allocatable :: table

type(toml_error), allocatable :: error

n_args = command_argument_count()

if (n_args > 0) then

call get_command_argument(1, config_path)

end if

call toml_load(table, config_path, error=error)

if (allocated(error)) then

print '(a)', error%message

stop 1

end if

call get_value(table, "parameter_1", parameter_1, stat=stat)

call get_value(table, "parameter_2", parameter_2, stat=stat)

call get_value(table, "output_dir", output_dir, stat=stat)

end subroutine load_config

end programThe Execution

With the interface in place, running the simulation was straightforward. I compiled all the Fortran code, and stored in blob storage, along with relevant metadata that identified the simulation and any required parameters. When the API received a request from a client containing a unique simulation ID and input parameters, it sent a message down a job queue, and a worker listening on the other end runs the simulation with the following steps:

- Download relevant simulation executable from blob storage

- Create a temporary directory containing the compiled simulation executable and output directory

- Write the user provided simulation parameters to a TOML file in the temporary directory

- Run the simulation executable

- Zip the contents of the output directory (populated with CSV files by the simulation)

- Store output zip in blob storage

This flow provides a simple framework that can be used to run any simulation, and it's all based on two simple rules: TOML in, CSV out.

The final piece of the puzzle was displaying the results. This was done with a combination of Vue and Quasar. I used Plotly.js to actually display the results. Much like any self-respecting backend/infrastructure engineer, this is the part that I enjoyed the least.

Results

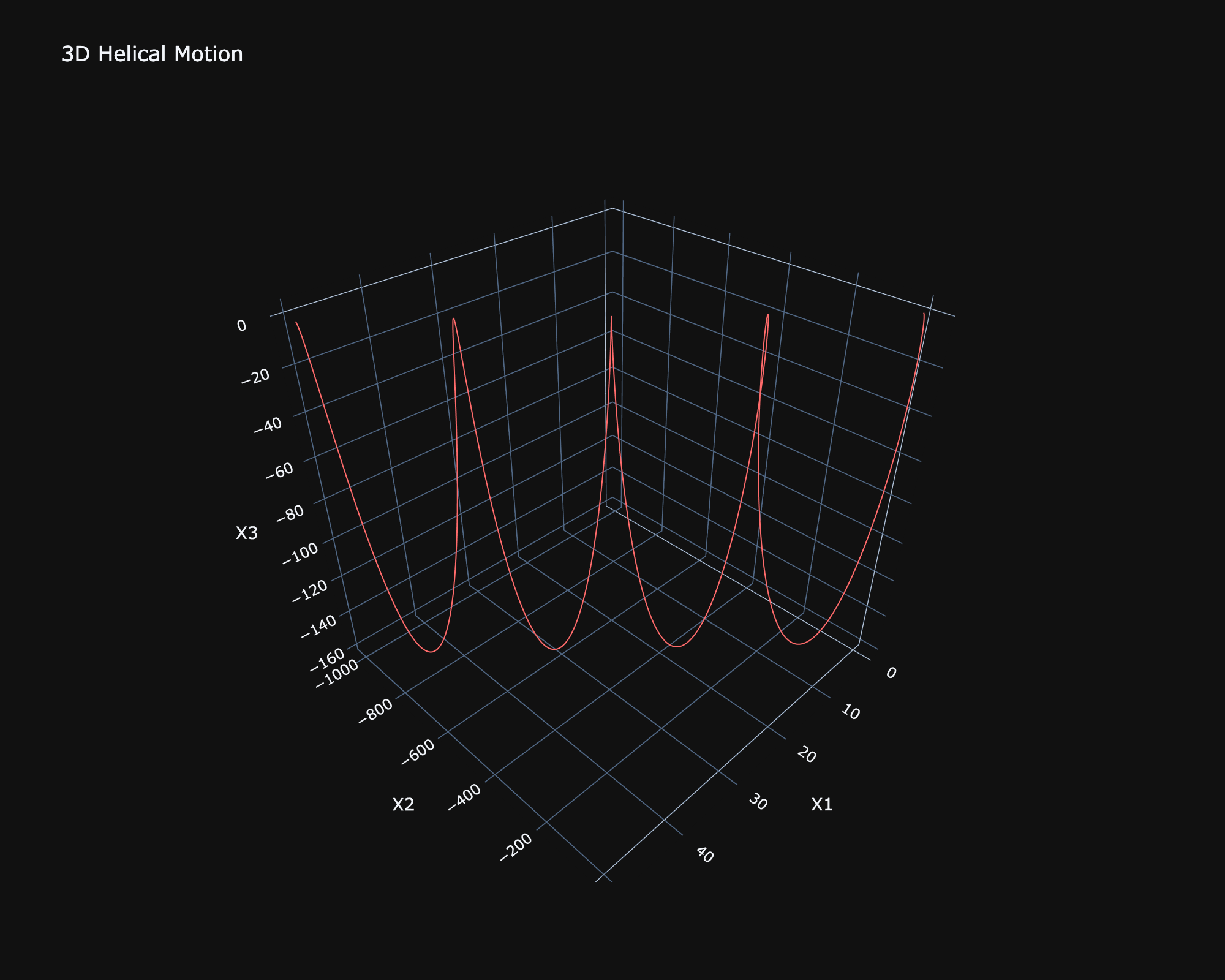

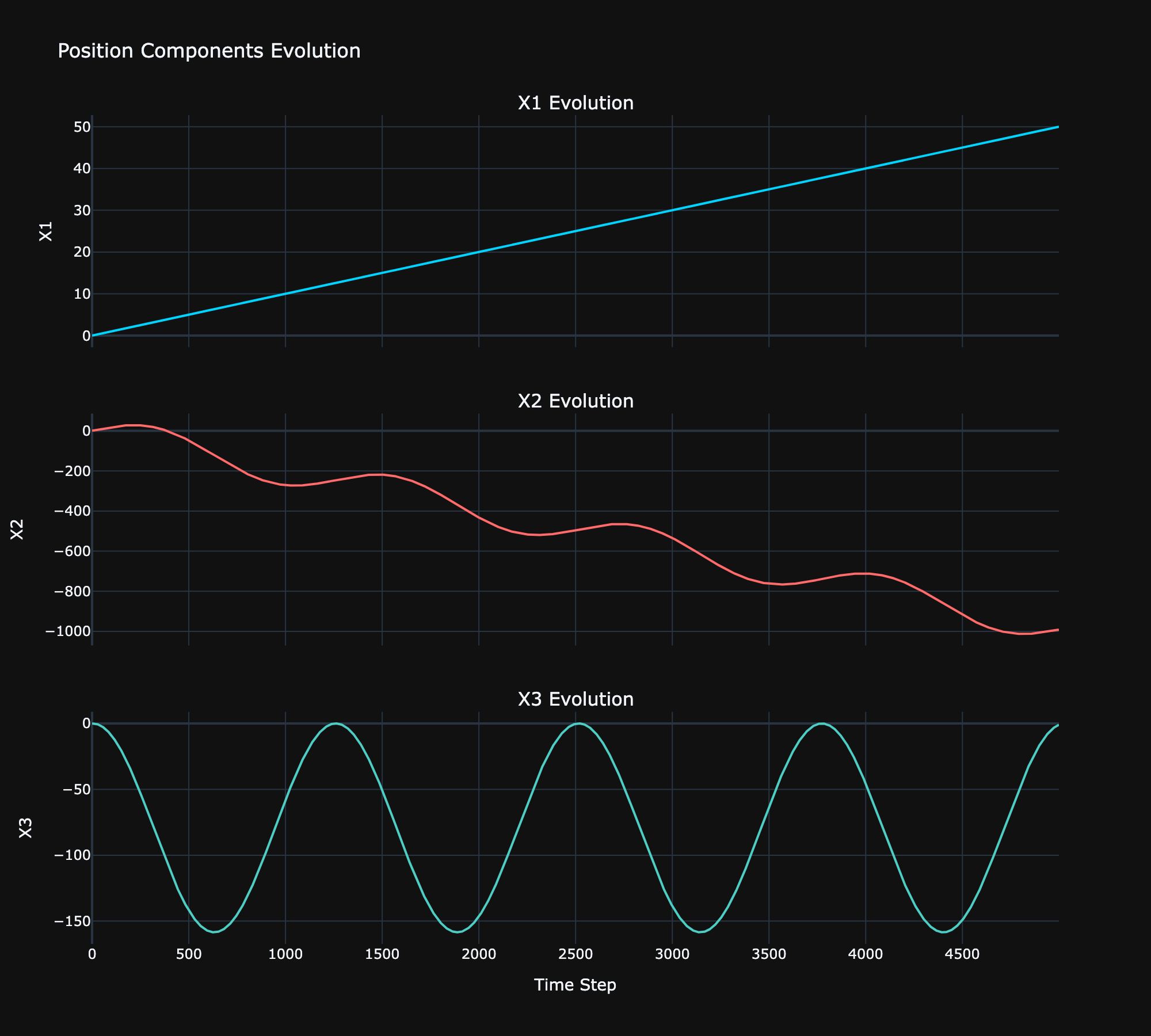

With everything in place, it was time to run some simulations. The following plots show the results of a charged particle moving through a uniform magnetic field. , and are used for the basis, and in this case correspond with cartesian coordinates , , .

3D trajectory of a charged particle in a magnetic field, showing the characteristic helical motion.

Time evolution of the particle's position components.

Figure 1 shows the helical motion created in the presence of a magnetic field. Note that the helix is compressed in the plane due to the addition of gravity.

Figure 2 shows the time evolution of the individual position components. The magnetic field was set to be aligned with the axis, resulting in a constant velocity in the plane. Both the and planes experience acceleration due to the magnetic field, producing the classic helical trajectory.

Figure 2 also clearly shows the horizontal drift created by the introduction of gravity.

Outcomes and Learnings

I set out to find a useful way to spend some down time and get away from the AI craze. And it has to be said, Fortran and Physics delivered.

The web development portion is what I do everyday, and these are arguably the least interesting components of the project. However, I'm happy with the overall framework and how it came together. The most important thing was to develop something that was generic so that I could in future focus on what really interested me: the physics and the Fortran. And I think to that degree, this initial implementation was a success. The current web app can run any Fortran simulation, provided it follows the TOML in, CSV out convention.

In regards to the Fortran and the physics, I learned two things:

- Keep the Fortran minimal

- Don't waste your time with Verlet Velocity in a magnetic field

Speaking to the first point, Fortran is not a general purpose language. It's hyper-optimized for numerical computing, and it's incredibly good at that. However, everything else can be a challenge. Keeping the Fortran code scoped to (1) read config, (2) run simulation, (3) output CSV, solved many headaches, and produced a clean, and maintainable codebase. The motto from there on very much became: let Fortran do what it's built for, do everything else in Golang.

As for the second point, I can't really speak ill of Verlet Velocity. It's incredibly easy to implement and works well for a whole host of systems. However, when magnetism is involved, just stick with Boris. It wasn't much harder to implement and produced far, far better results. This won't come as a surprise to anyone experienced in the field, but for a lowly web developer, it was quite the revelation.

That's it for today. For anyone who's interested, the entire codebase is available on my public GitHub: simulation-catalogue (API, worker, and web app) and simulations (Fortran physics engine).